I am standing lab-coated, scalpel in hand, staring at an esophagus covered in spikes. They look designed to eviscerate, like accessory teeth that might belong in the terrible maw of a creature from another planet in a science fiction movie. But the animal before me doesn’t have any teeth, just a beak; it is a Kemp’s Ridley sea turtle, and the odd looking papillae that line its esophagus allow it to eject ingested seawater without losing its lunch of mollusks and jellyfish.

Learning the anatomy of the dog and horse leave one only remotely prepared to understand the architecture of marine turtles and the myriad of other aquatic species. The AQUAVET® program is designed to bridge the chasm between terrestrial and aquatic medicine, and to impart in a few weeks what amounts to four semesters worth of information in the veterinary school curriculum.

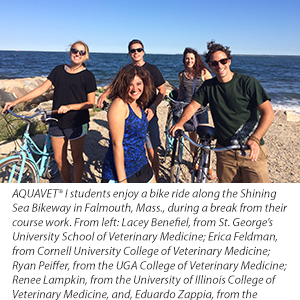

I arrived in Bristol, Rhode Island, on the irriguous campus of Roger Williams University at the end of May along with 24 other veterinary students and veterinarians from around the world. When I signed up for the summer course known as AQUAVET® I, I had envisioned a camp-like experience. In reality it turned out to be something of a mix between summer camp and boot camp.

Lectures ran from 8 a.m. until 8 or 9 p.m., with brief interludes for meals. And time was still pressed to cover the anatomy and physiology of aquatic phyla, from veligers—the ciliated larvae of bivalves, like oysters—to fish and marine mammals, as well as the etiology, pathology and treatment of their corresponding diseases. This information was presented from a number of perspectives, including the aquaculture of invertebrate and fish species for consumption and the commercial aquarium trade, the maintenance of animals on exhibit in public aquaria, the rescuing and rehabilitation of wildlife, and the care of client-owned animals.

The time in the classroom was punctuated by laboratory time, during which birds, snakes, turtles, fish, squid and caiman were dissected, among other aquatic animals. Fish were also surgerized with the use of apparatuses specially designed to deliver anesthetic-laden water to their gills during the procedure.

More exciting still were the field trips: from jaunts down to Mount Hope Bay to collect invertebrates from the intertidal zone to visits to research institutions and aquaria throughout New England. At the Woods Whole Oceanographic Institution’s Village Campus, on Cape Cod, we necropsied porpoises, dolphins and seals that had stranded on the beaches there the previous season. At the Long Island Aquarium and neighboring Riverhead Foundation for Marine Research & Preservation, we examined penguins under human care, as well as rescued seals that were subsequently released back into the wild. And at the New England and Mystic Aquariums we learned about managing the health of their extensive collections.

For all of the knowledge conveyed, one of the most informative parts of the program for me was to be able to socialize with a cohort of veterinarians who have forged somewhat alternative, yet infinitely interesting careers. The AQUAVET® program employs a constantly changing roster of instructors who are experts in their respective fields, and who are as happy to share the details of their career journeys as they are to share the technical information that they have gained, often over a hard-earned pint at the end of a long day.

As it always does, the time flew by. When the month-long didactic course ended, I bid farewell to my colleagues but remained in Bristol, trading the classroom for the laboratory—the Aquatic Diagnostic Laboratory at Roger Williams. Through research and diagnostic services, the lab supports both Rhode Island’s economically important shellfish fisheries and aquaculture programs, as well as the burgeoning tropical aquaculture program at the university.

Anecdotal data from fishermen, corroborated by scientific dredge surveys, had recently demonstrated an increased frequency of brown, track-like lesions in the ivory adductor muscle of scallops. Scallops—pronounced with an ‘aw’ sound from the back of the mouth in New England (you will be corrected with a sidelong glance for pronouncing it otherwise)—are an important revenue source for the region, and these blemishes made the meat less aesthetically pleasing, although not unsafe for consumption.

Initial studies had discovered larval nematode parasites in the muscle, and it became my task to identify these worms, both morphologically and molecularly. The primary suspect was a species of nematode that spends its larval stages in bivalves and other mollusks before they are consumed by sea turtles. The larvae then attach to the esophagus of the turtles between the spiky papillae, where they develop further and migrate down the digestive tract.

I count it as a point of pride that until this point in my academic career, I had been able to avoid almost entirely research that was even remotely molecular. And yet I found myself in possession of nematodes that had been plucked from cold-stranded sea turtles, ill-prepared to identify them and amplify and sequence their DNA. Two months being scant room for a research project of any sort, I spent much of my time learning the taxonomy of nematodes and gaining a practical and technical understanding of polymerase chain reactions (PCR).

The results of my work hold some promise for the development of a quantitative PCR to detect nematode DNA in scallops, although I suspect that the sum of it will prove more valuable to me than the output will to others and to future work. My research, along with the AQUAVET® course, served to reaffirm and deepen my abiding interest in the watery part of the world and the animals that inhabit it, and it is my hope that the program will serve as a foundation upon which to build a career in pursuit of those interests, as it has for so many others.