My experience in Indonesia began in late May at the Yogyakarta airport, when I was greeted by the smiling face of Adretta Soedarmanto, a third-year veterinary student at the  Gadjah Mada University, or UGM. Soedarmanto graciously volunteered to show me around UGM and help me settle in that day. I toured UGM’s facilities, receiving curious stares as I walked through hallways and courtyards. There was no chance of blending in as the only blonde in the vicinity. Although I stood out like an alien who had taken a wrong turn to Earth, I was welcomed by all who crossed our path. This day was filled with many “firsts”: riding a motorbike; eating a meal with my bare hands in a restaurant; leaving my shoes behind before entering a building, room, or someone’s home; hearing the Islamic Call to Prayer, and, being surrounded by a language of which I knew very little. I enjoyed soaking up the new sights, the busy noises of the streets and the hospitality of the people I met.

Gadjah Mada University, or UGM. Soedarmanto graciously volunteered to show me around UGM and help me settle in that day. I toured UGM’s facilities, receiving curious stares as I walked through hallways and courtyards. There was no chance of blending in as the only blonde in the vicinity. Although I stood out like an alien who had taken a wrong turn to Earth, I was welcomed by all who crossed our path. This day was filled with many “firsts”: riding a motorbike; eating a meal with my bare hands in a restaurant; leaving my shoes behind before entering a building, room, or someone’s home; hearing the Islamic Call to Prayer, and, being surrounded by a language of which I knew very little. I enjoyed soaking up the new sights, the busy noises of the streets and the hospitality of the people I met.

Just nine months earlier, I had arrived for orientation as a first-year student at UGA’s College of Veterinary Medicine, excited to be one step closer to becoming a veterinarian. Having developed a passion for traveling during my undergraduate years, I was determined to find a way to discover the world during my veterinary education. In orientation, I learned about the Certificate in International Veterinary Medicine program for UGA CVM students. To receive this certificate, students must complete certain courses, conduct a research-based project, be proficient in a foreign language and spend at least three weeks interning in another country.

Several months later, a fellow student, John Rossow (DVM 2017), emailed CVM students to encourage applications for the Asia-Georgia Internship Connection Grant through the Freeman Foundation. These grants are awarded biannually to students seeking to complete an internship of at least four weeks in a country in Southeast Asia. Ecstatic, I immediately began working on my application.

I had no connections of my own in Southeast Asia, but I was determined to find an opportunity. Dr. Corrie Brown, a professor of pathology who is a faculty advisor on the CIVM program, proved to be a great connection to many international veterinary colleges and she facilitated introductions to her colleagues across the world. Through Dr. Brown, I met and soon befriended Putri Pandarangga, a veterinarian from Indonesia who was getting her master’s degree in veterinary pathology at UGA. It was Pandarangga who connected me to Dr. Indar Julianto, director of international affairs at the UGM—the oldest and largest institution of higher education in Indonesia. Dr. Indar agreed to host me for UGM’s summer internship program and we began to plan my summer as the first American student to visit their veterinary school.

I had no connections of my own in Southeast Asia, but I was determined to find an opportunity. Dr. Corrie Brown, a professor of pathology who is a faculty advisor on the CIVM program, proved to be a great connection to many international veterinary colleges and she facilitated introductions to her colleagues across the world. Through Dr. Brown, I met and soon befriended Putri Pandarangga, a veterinarian from Indonesia who was getting her master’s degree in veterinary pathology at UGA. It was Pandarangga who connected me to Dr. Indar Julianto, director of international affairs at the UGM—the oldest and largest institution of higher education in Indonesia. Dr. Indar agreed to host me for UGM’s summer internship program and we began to plan my summer as the first American student to visit their veterinary school.

Thanks, in part, to Rossow, six CVM students spent summer 2015 in Southeast Asia. (For many of us, this was our first time writing a grant proposal, but our efforts paid off!) Rossow traveled to Laos and Thailand to develop a photo catalog of common lesions found in swine, cattle and Asiatic buffalo at slaughter. Julie Thompson (DVM 2018) conducted research with Salmonella and Campylobacter in wild birds with the Universiti Putra Malaysia in Malaysia. Scott Epperson (DVM 2018) worked to improve the protocols on avian influenza surveillance in humans in Bangladesh. Stephanie Howell (DVM 2018) and Amanda Morvai (DVM 2018) spent time volunteering and working with elephant veterinarians in northern Thailand. While we all traveled to the same region of the world, we had varying experiences with regards to both culture and veterinary exposure. (See sidebar starting on page 38 for photos from the other five internships.)

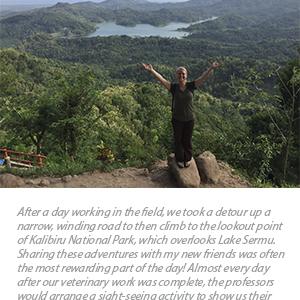

My internship time was divided between UGM’s small animal clinic and hospital, and the field. I usually worked with Dr. Slamet, a man who quickly demonstrated his indefinite amount of knowledge on any species we encountered, from cats to cobras to cattle. While at the clinic, I noticed the biggest difference between our facilities and theirs was the laid-back atmosphere at UGM. While there were always cases, surgeries or projects to work on, I never once saw anyone stressed or in a rush. The students always found time to get lunch, pray and—sometimes—nap! The rooms of the hospital surround an outdoor courtyard and the windows remain open, in hopes that a breeze will blow through the hot, humid rooms. I had the freedom to help in all areas of the clinic, assisting with whatever procedure I stumbled upon.

In the field, I was inspired by the students who worked to make a difference in the local communities. For instance, as part of a senior research project, the students educated  local farmers on the importance of nutrition for livestock. Most families on the island of Java own at least one cow that provides milk, meat and financial support for the family. Disposable income is not common in these areas and any increase in size or production can make a significant difference for these families. Cattle farmers are not always aware of the effects that proper care can have on their animals and this project encouraged them to increase efforts to provide nutritional supplements. The data collected for the project aimed to find a correlation between supplementation of specific minerals and the cows’ health. I appreciated seeing the students and veterinarians not only treat the cattle, but also spend time getting to know the farmers, understanding their practices and encouraging them to routinely monitor the health of their animals.

local farmers on the importance of nutrition for livestock. Most families on the island of Java own at least one cow that provides milk, meat and financial support for the family. Disposable income is not common in these areas and any increase in size or production can make a significant difference for these families. Cattle farmers are not always aware of the effects that proper care can have on their animals and this project encouraged them to increase efforts to provide nutritional supplements. The data collected for the project aimed to find a correlation between supplementation of specific minerals and the cows’ health. I appreciated seeing the students and veterinarians not only treat the cattle, but also spend time getting to know the farmers, understanding their practices and encouraging them to routinely monitor the health of their animals.

Regardless of whether they were in the field or the clinic, the ingenuity of the veterinarians and students regularly amazed me. The most high-tech materials and machinery were not available, but the doctors always got the job done with the simple tools to which they had access. For instance, I vividly remember the day I rode to the school with Dr. Slamet to help capture three macaques that had escaped their enclosure. We arrived to find students surrounded by colorful yarn, glue, tape, PCV pipe and syringes. Come to find out, they were making their own tranquilizer guns—from items you could find in an arts and crafts store! Although I was doubtful, the students successfully used their homemade blowguns to tranquilize and recapture the escaped macaques.

Learning how to examine a venomous snake and give injections to a crocodile were definitely challenging tasks, but my biggest challenge was the language barrier. Indonesian students are required to take English classes in grade school, but the level of comprehension and fluency varies greatly. There are more than 700 indigenous languages spoken in Indonesia, but Bahasa Indonesia is the official language has been used as a common language for centuries. My attempt at learning common Indonesian words and phrases was much appreciated by the students. Sometimes, I could jokingly trick students into believing I could speak their language, but this was nowhere near the truth and I continuously inquired into the topics of conversations. I tried to get to know each student I met, however, my best friends became those who had the most experience with English and could understand my sarcasm and humor.

Getting to know the Indonesian people, learning about their culture and appreciating their way of life had a huge impact on my personal growth. I made every effort to understand the Indonesian and Islamic culture by living as they lived. Indonesia is home to the largest Muslim population in the world and each morning starts off with the Call to Prayer being recited clearly over the city from the surrounding mosques. This call is heard four more times throughout the day, and the people make time in their schedules for these prayers. The sound of the call surprised me during my first days in the country, but soon became a soothing reminder of the need to step back and appreciate life in this beautiful country. Islam is entrenched in their culture, and the people are connected through their beliefs and united through their traditions. The Indonesians are among the most generous and caring people I’ve been fortunate to meet through my travels.

Getting to know the Indonesian people, learning about their culture and appreciating their way of life had a huge impact on my personal growth. I made every effort to understand the Indonesian and Islamic culture by living as they lived. Indonesia is home to the largest Muslim population in the world and each morning starts off with the Call to Prayer being recited clearly over the city from the surrounding mosques. This call is heard four more times throughout the day, and the people make time in their schedules for these prayers. The sound of the call surprised me during my first days in the country, but soon became a soothing reminder of the need to step back and appreciate life in this beautiful country. Islam is entrenched in their culture, and the people are connected through their beliefs and united through their traditions. The Indonesians are among the most generous and caring people I’ve been fortunate to meet through my travels.

Part of my stay coincided with Ramadan, a 30-day period devoted to fasting, introspection and prayer. When I first arrived, Dr. Indar apologized that I would spend my last week during this “time of fasting.” I wasn’t sure what this meant for me and was a little skeptical. But, the more I learned, the more excited I became to experience what life was like during Ramadan, when Muslims do not consume food or water from sunrise to sunset. I, too, fasted (for a few days). These days of self-control through my thirst and hunger gave me an enhanced perspective on the strength and the devotion of the Muslim people. My relationships with those around me also grew as we broke the daily fast together with beverage and food at each sunset.

My time in Indonesia was spectacular! Waking up each morning in a new country with a new day filled with unknown surprises strengthened my drive for never-ending adventure and learning. The kindness and acceptance of the students and professors made each day better than the last. While there, I learned I had received the Health Professions Scholarship through the U.S. Army Veterinary Corps. Knowing my career as a U.S. Army officer will bring opportunities to work around the world, I welcome a future of connecting with cultures far and wide.